The Composer’s Dilemma

When creating music for interactive games, the composer must take into account a number of additional considerations that do not usually present themselves when composing linear music. In linear music the composer is able to dictate the exact form and structure of the music, controlling the length of each musical section to ensure the piece flows and evolves in an effective manner. With interactive music, control of the musical structure is often handed over to the player, meaning that the composer must create music with this in mind. For example, a game may feature a section in which the player explores the level before entering combat. Clearly these two scenarios will require different musical accompaniment, with an effective and seamless transition between the two. Sweet (2015, p. 166) notes that the most effective video game scores serve to enhance the entire experience of playing the game, stating that “any music that does not support this goal will remind the players of the meta-reality instead of providing them with a cohesive narrative experience”. The dilemma for the composer in this situation is that the length of time the player spends exploring before entering combat is entirely under the control of the player themselves. As Collins (2008, p. 3) states: “While they are still, in a sense, the receiver of the end sound signal, they are also partly the transmitter of that signal, playing an active role in the triggering and timing if those audio events.” This means that the musical accompaniment must be flexible enough to allow for a number of eventualities, from the impatient player who rushes through the area to the player who stands still and listens to the score play out. The solution to this issue is to create a dynamic music system that is able to respond to the player’s actions in real time. Many approaches to this kind of dynamic scoring currently exist, but the focus of this article will be one of the earlier systems, which in some ways remains unsurpassed even to this day.

iMUSE – The Interactive Music Streaming Engine

In 1991 a system known as iMUSE was developed by composers Peter McConnell and Michael Land during their time working for LucasArts (Collins 2008, p. 51). The system was able to manipulate MIDI data in real time in order to create a dynamic musical underscore and was used in a number of LucasArts adventure games, most notably in Monkey Island 2: Le Chuck’s Revenge (LucasArts 1991) and Grim Fandango (LucasArts 1998). The difference in the way that iMUSE was used in these two titles is rather pronounced, and serves to highlight the advantages and disadvantages of moving from an entirely MIDI based approach to the use of pre-recorded audio files.

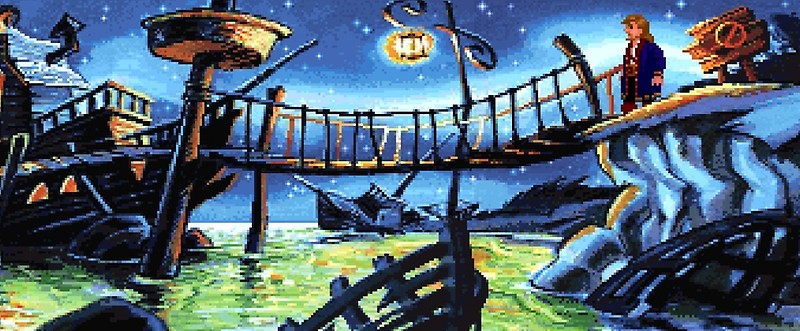

Monkey Island 2: The MIDI Approach

MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) is a protocol that allows for the remote control of digital instruments such as samplers and synthesisers. Unlike audio it contains only a set of instructions relating to how and when notes should be played, and does not represent the sound waveform itself (Rumsey and McCormick 2006, pp. 373-374). This carries with it the advantage of taking up relatively small amounts of hard drive and memory space, but also has the disadvantage of being limited sonically by the capabilities of the synthesiser or sampler to which the MIDI data is passed. MIDI also has a number of other advantages over digital audio, especially as far as the game composer is concerned. The musical underscore for Monkey Island 2 was composed and implemented entirely using MIDI within iMUSE, which allowed for seamless transitions between the game’s various musical cues. In its original implementation, iMUSE was essentially a database of musical sequences, each of which contained a number of musically related “decision points” at which the sequence could be altered in a number of ways. Instruments could be turned on or off, switched to different instrumental voices, transposed, sped up, slowed down, looped and synchronised to gameplay events (Collins 2008 p. 52). All of the above could be achieved by manipulation of the existing MIDI data, and most importantly without the creation of new audio assets. By contrast, if the composer wished to do something as simple as moving the melody from a violin to a clarinet whilst using pre-recorded audio, it would require the creation of two separate assets. The flexibility of using MIDI data in iMUSE is shown in the video below, where the player character moves between various different environments and the music changes accordingly at musically appropriate points.

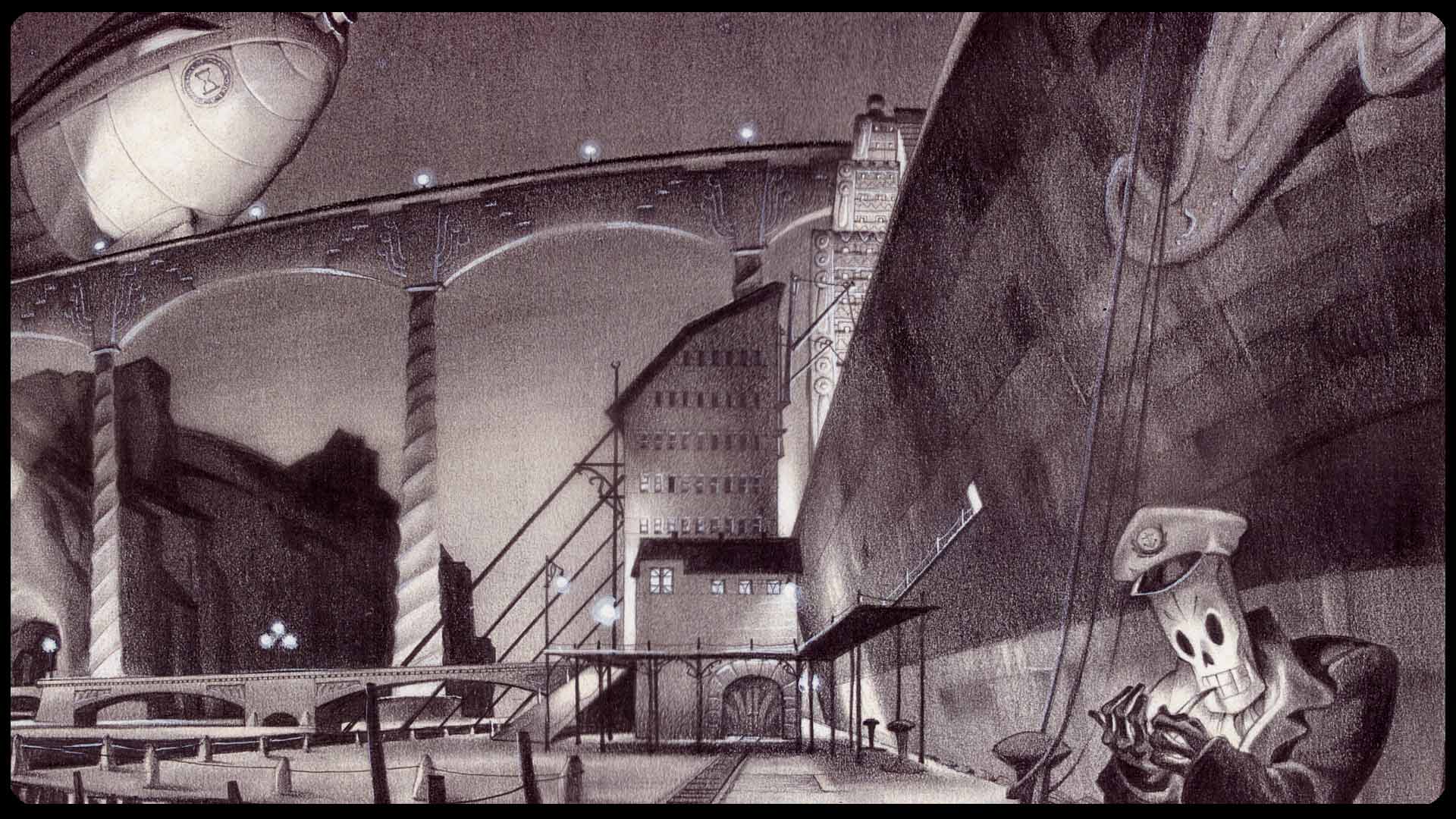

The Advent of Digital Audio: Grim Fandango

Grim Fandango was released in 1998, at a time when the CD-ROM was the standard medium for video game releases. This allowed games to make use of red book standard CD audio at 16 bit 44.1 kHz resolution. As Collins (2008, p . 69) notes, this technological shift resulted in an increase in the overall fidelity of sound at the expense of dynamic adaptability and interactivity. This is exemplified in the different approaches to transitions found in Monkey Island 2 and Grim Fandango. In an interview with Venturebeat (2015) composer Peter McConnell states: “I was always very proud of one aspect of the score, which was that we were able to do nice live jazz recordings”. The use of digital audio allowed for the capture of nuanced and dynamic musical performances which would have been incredibly time consuming if not impossible to create using MIDI instrumentation, however the ability to smoothly transition between cues was sacrificed as a result. As can be seen in the video below, transitions from one area to the next are handled by simply fading out one cue and fading in the next.

Monkey Island 2: Special Edition

Monkey Island 2 was remastered and re-released for the Playstation 3, Xbox 360 and PC and various mobile platforms in 2010, under the name Monkey Island 2: Special Edition (LucasArts 2010). During an interview with Audiogang (2010) music supervisor Jesse Harlin stated that when implementing the music for the special edition, they required a system that would work across all of the target platforms, thus precluding the use of MIDI. Digital audio was chosen to implement the music, leading to the creation of an updated version of iMUSE designed to apply it’s original functionality to digital audio. As can be seen in the video below, the end result is a system that very nearly matches the original iMUSE in terms of its transitional capability, but doesn’t quite achieve the same level of seamless transition as the original.

The Future Of MIDI in game scoring

Clearly MIDI still retains an advantage when it comes to dynamic audio transitions, and with the advances made in sampler instruments since iMUSE was first created in 1991, the shortfall in audio fidelity when compared to digital audio is decreasing rapidly. During an appearance on the Game Audio Podcast (2016), composers Guy Whitmore and Rodney Gates discuss the MIDI capabilities of the audio middleware package Wwise. They conclude that it is possible to implement MIDI in Wwise in an effective way, but there is a gap in the market for a standard Wwise sampler instrument that could be supported by major sample library creators. High quality sampler instruments also require large amounts of memory, for example Whitmore suggests that the minimum memory requirements for a convincing MIDI orchestra would be 1 gigabyte. This is (at the time of writing) a rather large amount of memory to dedicate to music. As system specifications increase and compression techniques improve this approach may well become a viable option, and there could potentially be a resurgence in adaptive MIDI scoring in mainstream games. Until then Whitmore and Gates recommend a “best of both worlds” approach, utilizing MIDI sparingly in conjunction with digital audio. Audio middleware tools such as WWise currently allow a lot of the functionality that iMUSE originally provided to be applied to audio, such as the fading in and out of musical elements based on game parameters and the transition between musical segments at musically appropriate points. When used in combination with the flexibility of MIDI, this joint approach could lend itself incredibly well to adaptive scoring.

REFERENCES

Collins, Karen (2008): Game Sound: An Introduction to the History, Theory and Practice of Video Game Music and Sound Design – The MIT Press, Cambridge MA.

Game Audio Podcast, The (2016): Episode #56: Rebirth Of MIDI – Online resource [Available at: http://www.gameaudiopodcast.com/?p=1203] Accessed 20/03/18

LucasArts (1991): Monkey Island 2: Le Chuck’s Revenge – LucasArts, San Francisco

LucasArts (1998): Grim Fandango – LucasArts, San Francisco

LucasArts (2010): Monkey Island 2: Special Edition – LucasArts, San Francisco

Rumsey, Francis and McCormick, Tim (2006): Sound and Recording: An Introduction – Focal Press, Oxford

Sweet, Michael (2015): Writing Interactive Music For Video Games: A Composer’s Guide – Addison Wesley, London

Venturebeat (2015): Grim Fandango’s Composer on the Invention and Remastering of his Classic Score – Online Resource [Available at: https://venturebeat.com/2015/02/09/grim-fandangos-composer-on-the-invention-and-remastering-of-his-classic-score-interview/] Accessed 20/03/18.